Introduction

How to Spell “Tai Chi”

Tai Chi was first documented in the early 20th century, and made available to English language readers in the 1940s. In that era, English-language writers used the “Wade-Giles system” to transcribe Chinese into the Latin alphabet.

Following the obscure rules of Wade-Giles, the proper way to write Tai Chi Chuan (太极拳) is actually “T’ai-chi ch’üan.” Casual writers omitted the diacritical marks, resulting in “Tai-Chi Chuan.”

A few decades later, translators adopted Hanyu Pinyin as the preferred romanization system. The proper formulation became “Tàijíquán.” Pinyin still uses diacritical marks; and they are still widely avoided, resulting in the popular modern spelling: Taijiquan.

Spaces are ubiquitous in written English and absent in Chinese. Formal rules exist for inserting spaces during translation. These rules too are disregarded in casual communication.

Considering all these factors, along with the multiple languages, dialects, and logograms used by native Chinese speakers… there are at least four different ways to spell any word in an English-language Tai Chi dictionary! There is not one single “most correct” spelling.

In this dictionary, we present common and modern spellings first.

How to Pronounce “Tai Chi Chuan”

Listen in Mandarin:

Listen in Cantonese:

Taiji and Quan

Quan (拳) refers approximately to a style of martial arts. However, a Quan has a distinctly Chinese relationship with ethics and health, spirituality, art and social relations. To equate it with a contemporary “martial art” is to distort its methods, history and goals.

Originally, Taiji Quan was the Quan developed by the Yang family (杨氏) during the 19th century. This is probably not its original name. We don’t know exactly when this honorific title was first assigned to the art, or by whom. Forgery and false histories are routine within Kung Fu culture.

Taijiquan rose to fame in the early 20th century. Gradually its definition was expanded. Quan traditions originating before the rise of Yang family were added in, along with Quan evolving afterwards. This included styles of the Chen (陈), Wu (吴), Sun (孙) and Hao (武) families.

As the name of “Tai Chi Chuan” gained worldwide prestige, more new styles were invented to capitalize on it.

See also: Is Tai Chi Really a Martial Art?

Ch’i, Qi, Chi and Ji

Taiji (太极) is an ancient Chinese philosophical idea. English speakers commonly spell and pronounce it as “Tai Chi,” while actually referring to Taiji Quan (太极拳).

Qi (气) is another Chinese cultural designation. Qi is also commonly spelled as “Ch’i” or as “Chi.”

There is no direct translation for either Taiji or Qi, because there are no words in English which carry the same meaning and context. A rough translation might explain Qi as “energy” and Taiji as “the inceptive polarity.”

The common English spellings of these words, have led many pupils to assume a close relationship. Some even speculate that Chi is at the very center of Tai Chi Chuan!

There is indeed a relationship between these ideas. Nevertheless, the “Chi” in “Tai Chi Chuan” is literally a spelling error. Qi 气 and Ji 极 are two entirely different characters. There is no 气 in 太极.

Chengyu Are Not Instructions

Early writings on Taijiquan are composed in terse, idiomatic expressions (chengyu). These poems and songs are open to a wide range of interpretation. They are meant to be clarified through the lens of a reader’s prior experience and personalized education; not to be understood in isolation.

For an example of the style, consider San ren cheng hu (三人成虎). This idiom says “three men make tiger,” but means “an absurd claim becomes credible after it is widely repeated.” Similarly cryptic or ambiguous phrases are common in Taijiquan text.

A literal reading of classic texts will not match the authors’ original intent. This caveat applies not only to interpretation by casual modern readers, but also to explanations by professional translators, scholars, and purported subject matter experts.

See also: The Tai Chi Classics: A New English Translation

Other Divergences in Meaning

Language evolves over time. The foundational terms of Taijiquan have accumulated various definitions over the past century. Their overloaded meanings conflict, and occasionally even contradict each other.

For example, the famous teacher Zheng Manqing wrote in Taijiquan Tiyong Quanshu (太极拳体用全书), that the secret of Taijiquan is in not using Qi. Zheng’s statement is inimical to the teachings of his own followers!

Context is essential.

Mistranslations and Fallacies

Taiji has been translated as “Supreme Ultimate.” This connotes first and largest. However it does not mean better than. Taijiquan thus cannot be translated as “The Ultimate Form of Martial Arts.”

As we have said earlier, Quan means boxing, but not exactly.

Taijiquan is sometimes explained as “a style of boxing created to demonstrate Taiji principles.” This is not so. Firstly, because the art predates its current name. Secondly, because there are no such things as “Taiji principles.” Taiji is an ontological model, rather than a moral imperative or scientific theory.

Taiji Quan does have its unique strategies, tactics and priorities; which may be labeled as principles.

Taijiquan jargon is commonly expressed in Mandarin Chinese. However, this does not mean the jargon is commonly understood by Mandarin speakers. Knowing Chinese does not make one a Taiji expert, any more than speaking English would make them a great basketball player.

Taijiquan is neither simple nor straightforward. Personal guidance from a qualified expert is needed. This dictionary can not, by itself, enable you to understand Taijiquan… but it will help.

Concepts and Theory

Ba gua (八卦) – Eight trigrams (☰ ☱ ☲ ☳ ☴ ☵ ☶ ☷).

Changquan (长拳) — Long Fist; a family of boxing styles, preceding and contemporary with Taijiquan.

Dao or Tao (道) — A path, order, or teaching.

Fang song (放松) — A release of unnecessary tension.

Gongfu or Kung Fu (功夫) — Skill developed through an investment of time and effort.

Guoshu or Kuoshu (国术) — A martial art with nationalist views and objectives.

Hunyuan (混元) — Primordial.

Jing or Ching (经) — A historically important text.

Neidan shu (內丹术) — Methods of internal alchemy.

Neijia Quan (内家拳) — The category of “internal” martial arts.

Qi xing (七星) — Seven stars.

Sanbao (三寶) — Three treasures (commonly referring to Jing, Qi and Shen).

Shu (书) — A book (without the esteemed status of a Jing).

Tiyong (体用) — An essence and its expression.

Taijitu (太极图) — A symbol depicting Yin and Yang, e.g. ☯.

Wushu (武術) — A martial art; or a performance-oriented martial sport.

Wu xing (五行) — Five phases; or five elements.

Xin (心) — Emotional mind; heart.

Xiu dao (修道) — Self-cultivation.

Yangsheng (养生) — Methods for cultivating health and longevity.

Yin yang (阴阳) — A split without separation.

Energy, Intention, and Force

Jin (劲) — A type of refined force.

Jing (精) — The material foundation of life and Qi.

Li (力) — Unrefined force; or any force in general.

Qi (炁) — To beseech (乞) the sky (天) for grain (米).

Qi (氣) — That which flows to moderate a living ecosystem (e.g. water cycle).

Qi (气) — The energy which facilitates a transformation. (See earlier definitions.)

Qigong (气功) — The skill of working with Qi; or a method of developing the skill.

Yi (意) — Intention.

Curriculum

Jibengong (基本功) — Basic training.

Taijicao (太极操) — Gentle exercises inspired by Taijiquan.

Dajia (大架) — Big frame.

Ding shi (定式) — Holding a posture.

Duilian (对练) — Partner training, such as forms, drills or sparring.

Taolu (套路) — A choreographed sequence of movements and postures.

Tuishou (推手) — Pushing hands.

Sanshou (散手) — Freestyle sparring, which typically includes both striking and grappling techniques.

Xiaojia (小架) — Small frame.

Zhan zhuang (站桩) — Standing like a post; or standing meditation.

Zuowang (坐忘) — A method of seated meditation.

Anatomy

Baihui (百会) — A point on the top of the head.

Dang (裆) — Crotch.

Huiyin (会 阴) — A point in the perineum.

Kua (胯) — The area around the hip joints.

Laogong (劳宫) — A point near the center of the palm.

Mingmen (命门) — A point between the kidneys on the back.

Shou (手) — Hand; or hand technique.

Tui (腿) — Leg.

Xia Dantian or Dan Tien (下丹田) — A point roughly behind the navel; or the lower abdomen in general.

Yao (腰) — The area around the lumbar spine; or waist.

Yongquan (涌泉) — A point near the center of the sole of the foot.

Classroom Terms

Baoquan li (抱拳礼) — Fist-covering salute.

Da leitai (打擂台) — An elevated competition platform.

Duanwei (段位) — A formalized Wushu grading and ranking system.

Dui budui (对不对) — Isn’t that right?

Duifang (对方) — Practice partner, or opponent.

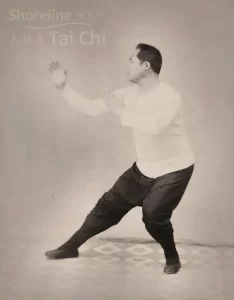

Hanfu (汉服) — Outfits (or costumes) historically worn by the Han Chinese people. These include the loose shirts and pants now associated with a “Tai Chi uniform.”

Kuai (快) — Fast.

Laoshi (老师) — Coach, or teacher.

Mianzi (面子) — Face; social standing.

Ni hao (你好) — Hello, how are you.

Shidi or Sidai (师弟) — Junior male classmate.

Shifu or Sifu (师傅) — Expert.

Shifu or Sifu (師父) — The master, in a personal master-disciple relationship.

Shijie or Sije (师姐) — Senior female classmate.

Shimei or Simui (师妹) — Junior female classmate.

Shixiong or Sihing (师兄) — Senior male classmate.

Tongxuemen (同学们) — Students.

Tudi (徒弟) – Disciple.

Wude (武德) — The ethical code of martial arts.

Wuguan (武馆) — Martial arts hall or school.

Zaijian (再见) – See you later.

Movements and Stances

Ao bu (拗步) — Twist step. Hand and foot advance on opposite sides, e.g. left foot with right hand.

Bai bu (摆步) — Swing step. The front toes open outward to the side.

Ban bu (半步) — Half step.

Ca bu (擦步) — Brushing step. The front foot slides on the ground.

Cha bu (叉步) — Crossing step. The rear foot moves sideways behind the front foot.

Chui (捶) — Punch.

Ding bu (定歩) — Fixed step.

Gen bu (跟步) — Follow step.

Gou shou (钩手) — The hook hand in the Single Whip posture.

Gong bu (弓步) — Bow stance. Body weight carried on the front leg.

He bu (合步) — Matched stance (e.g. your right leg forward, partner’s right leg forward). Compare to shun bu.

Huo bu (活步) — Moving step (not fixed step).

Jiao (脚) — Kick; or foot.

Jin bu (進步) — Forward step.

Kai bu (开步) — Opening stance.

Kou bu (扣步) — Pigeon-toed step. The front foot turns inward.

Lan que wei (揽雀尾) — Grasp the Bird’s Tail.

Ma bu (马步) — Horse stance. Legs are typically parallel and body weight is evenly distributed.

Pu bu (仆步) — Drop stance. Low squat with the front leg extended.

Shi tui zhuan ti (实腿转体) — Turning on a weighted leg.

Shun bu (顺步) — Opposite stance (e.g. your right leg forward, partner’s left leg forward).

Tui bu (退步) — Backward step.

Xu bu (虚步) — Empty stance. Body weight carried on the back leg.

Xu tui zhuan ti (虚腿转体) — Turning on an empty leg.

You (右) — Right side.

Zhongding (中定) — The center “step” around which other steps (wu bu) are made.

Zhou (肘) — Elbow.

Zuo (左) — Left side.

See also: Yang Style Tai Chi Postures List

Skills and Powers

Chan si jin (缠丝劲) — Spiraling, “silk-reeling” Jin.

Dong jin (懂劲) — Understanding Jin.

Fa jin (发劲) — To apply Jin, such as with an explosive strike.

Hua jin (化劲) — Neutralizing Jin.

Jindian (劲点) — Point of Jin.

Jinlu (劲路) — Pathway of Jin.

Ting jin (听劲) — Listening or sensing Jin.

Weapons

Dao (刀) — A single-edged blade. May be straight or curved.

Jian (剑) — A double-edged straight sword.

Gun (棍) — A long staff or pole.

Qiang (枪) — Spear.

Tie shan (铁扇) — Iron fan.

People and Places

Chenjiagou (陈家沟) — Chen Family Village.

Chen Weiming (陈微明) — An influential teacher and author of books on Yang style Taijiquan.

Huang Zongxi (黄宗羲) — 17th-century author of the earliest known reference to Neijia. At the time, neijia probably meant “indigenous to our culture” rather than “inside the human body.”

Jianghu (江湖) — The martial underworld culture, real and/or fictional.

Li Tianji (李天骥) — An architect of 24 Forms Simplified Taijiquan, and coach for the Chinese national wushu team.

Qi Jiguang (戚继光) — 16th-century Chinese military general and author.

Shaolin (少林) — A forest in Henan, China, with a famous Buddhist monastery; the martial arts practice associated with Shaolin Temple.

Sun Lutang (孙禄堂) — Inventor of Sun style Taijiquan; proponent of modern neijia theory.

Tang Hao (唐豪) — 20th-century historical scholar of Chinese martial arts.

Tianjin (天津) — City in northern China. A hub for the early dissemination of Taijiquan.

Wang Zongyue (王宗岳) — Author of a fundamental Taijiquan text.

Wudang or Wu Tang (武当) — A mountain range in central China; a tradition associated with temples in those mountains.

Wu Yuxiang (武禹襄) — Founder of Wu-Hao style Taijiquan; author of Tai Chi classics.

Yang Chengfu (杨澄甫) — Third-generation master of Taijiquan, responsible for popularizing the art inside China.

Yang Luchan (杨露禅) — Founder of Yang style Taijiquan.

Yongnian xian (永年县) — Yongnian County, Hebei Province. Birthplace of Yang Luchan.

Zhongyang Guoshu Guan (中央国术馆) — Central Guoshu Institute; a cross-disciplinary school for the advancement and preservation of Chinese martial arts.

Zhang Sanfeng (张三丰) — Legendary Daoist and creator of Taijiquan.

Zheng Manqing or Cheng Man-ch’ing (郑曼青) — College professor who spread Taijiquan in Taiwan and New York.

Phrases and Idioms

See also: The Tai Chi Classics: A New English Translation

Ba fa wu bu (八法五步) — Eight methods and five steps; an oblique reference to Taijiquan. Also, a specific taolu.

Bu ding, bu diu (不顶不丢) — Do not butt in; do not leave.

Bugang (步罡) — Ritually pacing through patterns, such as following the seven stars of the Big Dipper.

Chazhihaoli, miuzhiqianli (差之毫厘,谬之千里) — Off by a hair at the start, missed by a mile at the end.

Chen jian zhui zhou (沉肩坠肘) — Sink shoulders, drop elbows.

Chi ku (吃苦) — To suffer hardships.

Chi kui (吃亏) — Commonly mistranslated as “invest in loss.”

Dong zhong qiu jing (动中求静) — Find stillness in movement.

Dui niu tan qin (对牛弹琴) — Playing the lute for a cow.

Fen xu shi (分虚实) — Distinguish empty and full.

Guzhuang xi (古装戏) — Historical costume drama.

Hua quan xiu tui (花拳绣腿) — Flower fist and brocade leg; beautiful but useless technique.

Jin zhi ze yu zhang; tui zhi ze yu cu (进之则愈长; 退之则愈促) — Advancing, it seems too far; retreating, it seems too near.

Jing ru shanyue; Doing ruo jianghe (静如山岳; 动若江河) — Still like a mountain; moving like a river.

Jiu qu zhu (九曲珠) — Nine-curved pearl; an intricate passage.

Kai he (开合) — Open and close.

Li ru pingzhun; huo shi chelun (立如枰凖, 活似车轮) — Stand like a steelyard (scale); move like a wheel.

Mian li cang zhen (绵里藏针) — Needle hidden in cotton.

Neng pian jiu pian (能骗就骗) — If you can cheat, then cheat.

Pian laowai (骗老外) — Cheating foreigners.

Shi san shi (十三式) — Thirteen powers.

Shuang zhong (双重) — Double-weighted.

She ji cong ren (舍己从人) — Abandon one’s plans to follow another.

Si liang bo qian jin (四兩撥千斤) — A big return on a small investment; four ounces deflects one thousand pounds.

Si zheng (四正) — Four cardinal Jin, i.e. Wardoff (掤), Rollback (捋), Press (挤) and Push (按).

Si yu (四隅) — Four corner Jin, i.e. Pluck (採), Split (列), Elbow (肘), Shoulder (靠).

Ti da shuai na (踢打摔拿) — Kick, punch, throw, lock. The ancestor of “mixed martial arts.”

Wo xin chang dan (卧薪尝胆) — To strengthen oneself by voluntarily enduring hardship; sleep on sticks and taste bile.

Wushi bu xiao bai bu (五十步笑百步) — A fifty step [deserter] laughing at a one hundred step [deserter].

Wu shi you tu ao chu (毋使有凸凹处) — Do not allow protrusions or hollows.

Xu jin ru zhanggong; Fa jin ru fang jian (蓄劤如张弓; 发劤如放箭) — Store Jin like drawing a bow; release Jin like loosing an arrow.

Xu ling ding jin (虚灵顶劲) — An empty, lively Jin at the top of the head.

Yao kua fen li (腰胯分离) — Yao and kua must separate.

Ye Gong hao long (叶公好龙) — To flaunt your association with something, but flee the real thing itself.

Yicun chang, yicun qiang (一寸长一寸强) — One inch longer (is) one inch stronger. Usually referring to weapons.

Yi dan, er li, san gongfu (一膽二力三功夫) — Courage first, power second, technique third.

Yi dao qi dao (意到气到) — Yi dao qi dao.

Yidong quandong (一动全动) — One part moves, everything moves.

Yi ri wei shi, zhongshen wei fu (一日为师,终身为父) — A teacher for one day, a father for life.

Yi yu buneng jia, ying chong buneng luo (一羽不能加, 蠅虫不能落) — One feather cannot settle, a fly cannot alight.

Yong yi bu yong li (用意不用力) — Use Yi, not force.

Zhan, nian, lian, sui (粘黏连随) — Stick and follow.

Zhong ti xi yong (中体西用) — Chinese knowledge is essential; Western knowledge is instrumental.

© Shoreline Tai Chi. All rights reserved.